What would the first Tories have made of it?

A report published on 4 October 2014 by the union Unite [http://www.unitetheunion.org/news/tories-in-15-billion-nhs-sell-off-scandal/] has found that, since 2012, £1.5 billion of NHS funds has been contracted to private companies linked to 24 Tory MPs who voted for the Health and Care Act. Such contracts are legal; but is this very close relationship between elected representatives and private interests a form of corruption?

At the very least there is an irony here. The first Tory party, created in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, was highly critical of party politicians (their rivals, the Whigs) who sought to hoover up state assets by giving themselves lucrative contracts. At that period, of course, there was no national health service; but large amounts of government funds were spent on war with Louis XIV’s France and the same issue of contracts was at stake.

In December 1711, just over a year after the Tories had won a landslide electoral victory, a prosecution was launched by them against the duke of Marlborough, the military hero whose services to the country had been recognised with the gift from the nation of Blenheim Palace. To be sure, there was politics involved – Marlborough had been a Tory but had moved closer to the Whigs, and the Tories sought revenge. Marlborough's wife, the redoubtable Sarah, was also close to the Whigs. But in any case, the point at issue was a contract that the duke had to supply the army with bread, from which he made a 6% profit. Between 1702 and 1711, he received £62,000 (roughly the equivalent of about £5m in today’s money). Here, then, was public money being diverted into a contract from which Marlborough personally gained (and he had several crony friends who had also procured lucrative contracts to provide the army with clothing and supplies). The first Tory party was outraged. Jonathan Swift, by then a Tory partisan, satirised Marlborough’s avarice in his poem The Fable of Midas – the mythical king whose touch turned everything to gold – and in pamphlets Swift alleged that Marlborough, like other Whigs, was intent on profiteering from the war. Indeed, the object of the Tory attack included the whole new financial system – including the Bank of England that had been a Whig creation in 1694 – which Tories saw as a device to transfer wealth into the hands of their political enemies. ‘Corruption’ was a Tory rallying cry in the early eighteenth century, both in the reign of Queen Anne and then during the premiership of Robert Walpole, who was another of those prosecuted alongside Marlborough for his share in the contracts scandal and was expelled from the House of Commons for his ‘notorious corruption’.

The first Tories, then, saw it as their patriotic duty to oppose the corrupt and self-interested transfer of state funds into the hands of cronies by means of dubious contracts. What would they have made of today’s Tory party?

The text of the 1711 report into Marlborough’s contracts can be read at http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=tFMyAQAAMAAJ&pg=PT547&lpg=PT547&dq=1711+marlborough+contracts&source=bl&ots=7a69mwUvNu&sig=Gbfji9vU6ZhTNE0pLway3QPNALc&hl=en&sa=X&ei=-noxVNjcKcLO7gbJ44CwBg&ved=0CDoQ6AEwBQ#v=onepage&q=1711%20marlborough%20contracts&f=false

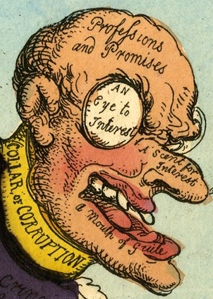

Image: A playing card satirising the duke of Marlborough as a money-making ‘rogue’

Mark Knights

Mark Knights

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…