All 1 entries tagged Network;

No other Warwick Blogs use the tag Network; on entries | View entries tagged Network; at Technorati | There are no images tagged Network; on this blog

January 01, 2023

Corrupt Lives? No. 1: Valentine Jones, ‘The Prince of Peculators’

Corrupt Lives 1: Valentine Jones, ‘The Prince of Peculators’

This is the first in a series that uses historical case studies to raise ethical questions, relevant to today, about corruption, anti-corruption and good governance.

Are people intrinsically corrupt or are they corrupted by others and the culture of corruption in which they find themselves? What is the difference, for a government contractor, between a fair profit and one that exploits the public purse, particularly during a time of national emergency such as a war, when there is a need for urgent supply of services and goods? How far might political considerations shield those who are intent on exploiting their public offices for private gain? These are the questions raised by the career of Valentine Jones.

When Jones had been appointed in 1795 as the commissary-general and superintendent of stores for the army based in the Leeward Islands in the West Indies, it was ‘supposed with clean hands.’ He had ‘served in divers public situations of credit, trust and responsibility’ in the West Indies, acquitting himself ‘with general satisfaction and approbation’. When the government gave him his role overseeing the logistical supplies for soldiers, he had been expressly told by George Rose, the treasury secretary, that he should not ‘derive the smallest advantage, in any shape or mode whatever, from your situation beyond your pay, on pain of instant dismissal'. Rose had sent the letter because he was ‘aware of the importance of securing to the public the services of respectable men in a part of the world where it had been found so difficult to check or correct abuses’. Initially Jones seems to have understood this and had written to his assistant commissary, Michael Sutton, to ensure ‘the proper application of the funds entrusted at any time to you, and the frugal expenditure of public money’.

1781 detail from a map of the Caribbean © The Trustees of the British Museum

But as early as 1797 there were warning signs. That year Rose wrote to Jones censuring him for ‘the serious and alarming Inconveniences occasioned by the immense Sums’ of public money he had drawn down ‘without any Notice or Warning whatever’. Although government acknowledged that conditions of war might make it impossible for him to submit ‘regularly detailed Accounts’, this did not mean that he could simply abandon ‘vouchers’ (paper receipts) altogether or neglect to provide ‘a strict Account’, as well as proof of the going market rate for goods, ‘as it essential the Public should be guarded against Waste or Fraud’. What Jones had been charging for rum ‘appears enormous’ – he had spent £376,000 in just ten months on spirits and other provisions. He was warned that his tenure of office was under review.

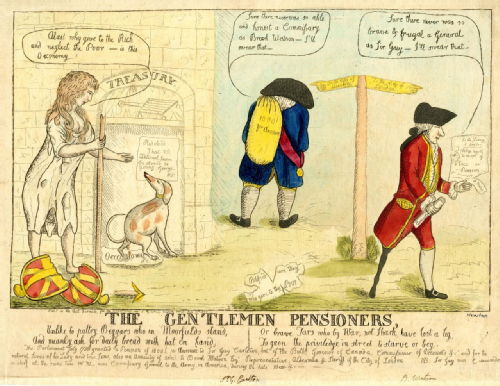

The Gentlemen Pensioners (1786), a satire showing Britannia impoverished by war and the profits made by an earlier commissary-general of Canada, Brook Watson, who was widely thought to have profited from the American war. His leg had been bitten off by a shark, hence his wooden peg. © The Trustees of the British Museum

Jones had conflicts of interest that undermined his impartiality. He was the son of a Barbados wine, rum and sugar merchant whose relatives ran a thriving import company in Belfast. Mercantile business ran in his blood and commercial considerations seem to have quickly got the better of him. He was approached by Matthew Higgins, who already enjoyed contracts for the armed forces and used an intermediary, Hugh Rose, to broker the deal (Rose was allowed a quarter of the profits, Higgins the other quarter, and Jones took half). Jones’s profits were also boosted when he established a ‘house in America, consisting of the names of Bennett and Carey; and with that house at Philadelphia he transacted this business’ of profiting from supplies there.

When in 1802 the government in Britain began investigating rumours, Jones had written to his successor, John Glasfurd, asking him to ensure that his accounts tallied with Jones’s, a request that he asked him to keep secret, ‘not that I should fear fair and candid investigation,’ for he was ‘conscious that our proceedings had not the evil intention that our judges believe; but I have already seen too much ill-will on this side of the water [ie in England] not to suspect foul play on the other.’ He even recommended a formulation for Glasfurd to employ to evade questions: ‘one general answer in your power… is, that you cannot remember the points of business so long gone by’.

'The Taking of the French Island of Martinique in the French West Indies on Feby 24th 1809'. Coloured woodcut, published by G Thompson, London, 17 June 1809., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In 1809 Valentine Jones was, finally, tried for ‘a corrupt bargain’ with Matthew Higgins. The latter had agreed to pay Jones a share of the profits he made on contracts for supplying the 30,000 troops stationed there in the 1790s. In March 1797 Jones had received £153,273 West Indian money, roughly £87,000 in sterling, over just a ten-month period. His case illustrates the difficulty of monitoring expenditure far away from the metropolitan gaze. The Attorney-General said that since Jones’s abuses had taken place ‘at a distance from the eye of those who have an immediate interest in preventing practices, frauds are easily committed; and it is very difficult when they have been committed to detect them.’

Jones’s defence argued that although he had been charged with ‘a breach of public trust’, he had exercised other situations of public trust in the West Indies ‘in all of which he had conducted himself with unblemished integrity’. Indeed, character witnesses called him ‘a very correct man’. But the Attorney General countered that

men who in other respects may conduct themselves honourably and uprightly towards those with whom they have communication, feel themselves unrestrained in any transactions which they may have with the public, and suppose that neither their character for honour nor integrity is impeached by practising the grossest frauds, provided those frauds affect only the public purse.

The impersonality of the ‘public’ thus seemed to liberate corrupt inclinations that were constrained by personal relationships.

The defence claimed that Jones had simply enjoyed lawful profits:

though in point of law it is not to be justified, in point of practice we know, it has happened, that men who have meant to do honestly and fairly have become interested with those who have provided the supplies for the public service upon a feeling, however false, and upon a footing not to be justified, but believing that if they merely shared in the fair profits, they committed no offence.

Thus technical illegality was not seen as such if the profit was merely a ‘fair’ one. The prosecution nevertheless showed that Higgins had made 30% profit, which was excessive.

Jones’s illicit profits had been unearthed by the commissioners of military enquiry, and his prosecution was hence an apparent victory for successful regulation by a watch-dog. The commissioners found that Jones may have got into bad habits when acting as clerk to the deputy paymaster in the West Indies, Mr Graeme, who profited on the rate of exchange on the public money he received (he was deputising for an absentee post-holder who pocketed the £400 salary). Graeme had been succeeded by Hugh Rose (no relation of George), who had continued the practice of profiting from any money made when the exchange rate was higher than its average, but also invested public money in produce, hence the contract with Higgins. The inquiry revealed a world in which a network of contacts was important but also one where making use of public money for private gain, and mixing public and private interests, were considered a routine practice.

The commissioners also found that it had been relatively easy to get away with ‘a regular and unchecked system of peculation, carried on in the most unblushing manner’. This in turn raised questions for the commissioners, or the predecessors. Critics said that they were an expensive and largely ineffective board that had failed to act even when abuses had been revealed. Indeed, vast sums of public money in the West Indies – over £7m for St Domingo alone - remained unaccounted for. Even the officer established as a check to corruption had become instrumental in it: instead of going to the West Indies, as he had been ordered, Isaac Phipps had employed deputies and then received half of whatever his deputies illicitly made in back-handers.

This complicit negligence had allowed Jones to develop ‘by means of combinations and intricacies almost impervious, an overruling and high injurious influence over the whole transactions of the public’ extending into ‘a far-extended system.’ Indeed, Jones profited every which way, since he was officially paid a good salary (£1000) and a 5% commission on whatever supplies he handled. The trial showed that he had defrauded the state of at least £87,000, though the likely figure was much higher.

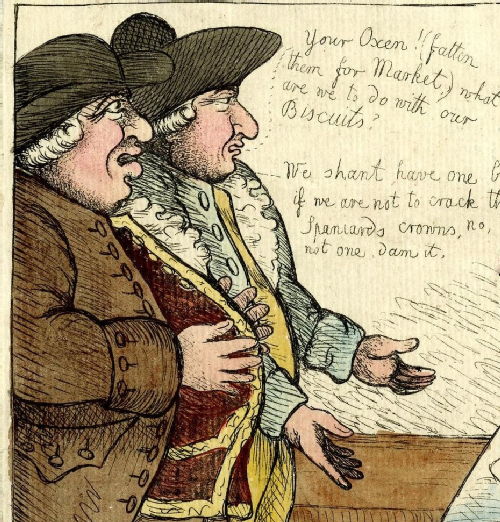

Navy Victualler and Contractors(1790) © The Trustees of the British Museum

Jones, nicknamed the ‘Prince of Peculators’ by one periodical, was given a three-year prison sentence, which the judge said was necessary ‘to prevent future peculation’ (peculation is an older word for embezzlement of public money by one entrusted with it). But he was not made to repay the money he had purloined and hence the leniency was criticised. Indeed, the press made Jones’s case a cause célèbre. In 1817 the radical author and publisher William Hone, facing trial for his own attempts to satirise government corruption, fumed against Jones as a ‘defaulter’ who had got away with his crime.

Hone showed that Jones was part of a gang of men, all loyal to Prime Minister William Pitt and shared anti-reform sentiment. Thus Hone linked Jones to a network of Pittite peculators. These included Oliver De Lancey, who had defaulted on £97,000 but had been rewarded with a pension of £2000; Thomas Steele, the army paymaster who made use of £19,800 of public money for seven years, even though he remained a privy councillor and Kings Remembrancer of the Exchequer on a salary of £830; John Glasfurd, who had failed to account for a sizeable part of the £6m that had passed through his hands; Isaac Phipps (as deputy paymaster general in the West Indies), who defaulted on £70,000; George Villiers who ‘lived like a Nabob till he was found out’ and owed £280,000 by 1804; William Bassett Chinnery, who defrauded the government of £80,000 and ‘gave sumptuous dinners and entertainments and balls’ for his cronies; and Charles Greenwood, an army agent and ‘instrument of corruption’ who had an official salary of £530pa but cleared at least £60,000, in collusion with the duke of York, commander-in-chief of the army who probably shared the profits or at least borrowed heavily from him.

What united these men and others, Hone claimed, was their anti-reform politics and loyalty to Pitt. Thus ‘Under Mt Pitt, Corruption flourished as in a hot-bed, and all the robbers were loyal, every man of them’. Hone thus used the press, even when he was himself under prosecution, to claim that there had been a widespread loyalist conspiracy to defraud the nation and to cover this up. Hone sharpened his attack, predicting that things would end ‘in real reform, in revolution or in despotism.’ Hone identified another of the corrupt crew as Alexander Davison, a close friend and agent of Admiral Nelson – Davison will be the subject of another blog.

What then are we to make of Jones?

He had previously enjoyed a seemingly good record of public service but became corrupted when opportunity, a conflict of interest and a general culture of corruption coincided with a lack of oversight. The conflict of interest was inevitable because it was precisely Jones’s business connections that had made him useful to the government. Knowing this, the government needed – for him and the other contractors on whom they relied - to take additional precautions, particularly as oversight from thousands of miles away was difficult, especially during the war-time conditions of the wars against Revolutionary and Napoleonic France.

The case suggests that robust mechanisms need to be in place before an emergency places strains on the system that open the way to corrupt activity – a problem we have seen with the PPE scandals in the UK when unscrupulous private agents profiteered from the public emergency, apparently with government sanction because the urgency of need was thought to outweigh the need for proper safeguards. And the case also shows that oversight mechanisms can themselves become corrupted, requiring constant vigilance.

The conflict of interest also meant that deciding on a ‘fair’ profit for a government contractor was - and still is - essential. His contract stipulated 2.5% but he clearly saw this as inadequate and pushed it over ten times higher. Was 2.5% sufficient, given the challenges involved in the supply of commodities? This was a debate that the government of the day – and now, given the large profits (8-10%) made by private prisons, for example – shied away from. How far is the public always dependent on such private outsourcing and is their profit corrupt?

The Jones case uncovered a network of individuals lining each other’s pockets and united by a shared ideology that opposed reform to the system from which they benefited; and the suspicion was that they enjoyed political support. Whilst the investigations were proof that the ‘elite’ was not monolithic and could expose corruption within its own ranks, the limited penalties only served to intensify suspicion of a corrupt ‘system’ that was lenient on insiders. Prime Minister Pitt thus offered something of a failure of leadership: although not personally corrupt, many of those allied to him were, and his administration was unwilling to take sufficiently robust action against them, in part because such men were deemed necessary to the war effort.

Further Reading: The Derby Mercury no. 4019, 1 June 1809; Thomas Howell, Complete Collection of State Trials xxxi (1809-13), 251-336; The State of the Nation with Respect to its Public Funded Debt, Revenue and Disbursement (1798), ii. 318-9, Rose to Jones, 10 May 1797; The New Annual Register, or General Repository of History, Politics, and Literature, xxx (1810), 264-5; The Seventh Report of the Commissioners of Military Enquiry (1809); Jackson’s Oxford Journal 2930, 24 June 1809; The Examiner 78, 25 June 1809; The Reformists’ Register 11 Oct. 1817 in Proceedings against William Hone before his trials (1817); Cobbett, Political Register xvii. 127; Mark Knights, ‘”Was a laugh treason?”: Corruption, Satire, Parody and the Press in Early Modern Britain’ in Knights and Morton, The Power of Laughter and Satire in Early Modern Britain (2017); Knights, Trust and Distrust: Corruption in Office in Britain and its Empire 1600-1850 (2021); Mentoriana; or, A letter of Admonition and Remonstrance, to His Royal Highness the Duke of York, relative to Corruption (1807).

Mark Knights

Mark Knights

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…