All 1 entries tagged James

View all 8 entries tagged James on Warwick Blogs | View entries tagged James at Technorati | View all 1 images tagged James

June 27, 2024

Political Bets

One of the issues that has cut through in the 2024 general election has been the scandal over political bets. A number of Tories associated with Number 10 Downing Street are under investigation for, allegedly, betting on the date of the general election and possibly seeking to profit from insider information about when it would be called. At the time of writing this blog, four people associated with the inner circles of the Conservative Party are under investigation and a police officer, attached to the PM’s close protection team, is suspended, pending investigation. The bets seem to epitomise Tory sleaze and the pursuit of self-interest by political insiders.

Betting on political issues using insider knowledge is not, however, new. Just over three hundred years ago, the close associates of John Churchill, the first duke of Marlborough (and ancestor of Winson) profited from placing rather similar bets. But they were not found out or publicly named. At least, not in their own life-times.

The evidence of their wagers emerged in 1951 in an article by Godfrey Davies on the ‘seamy side’ of the war of Spanish Succession (1702-1713). Marlborough was the Commander-in-chief of the armed forces fighting France in a war fought not just in Europe but also in the Caribbean. One of his key allies was James Brydges, Paymaster of the Forces, who made a fortune because his office entitled him to a percentage of all the money that passed through his hands. Since the war was the most expensive Britain had ever fought – in part because it was a land war as well as a naval one – Brydges made about £600,000 (the equivalent of about £63 million today), though this fortune was also, as we shall see, the result of a whole series of questionable activities that sailed very close to the wind. Brydges was in frequent correspondence with William Cadogan, Marlborough’s quarter-master general. The subject of their letters was how to profit from the war. Both men were MPs and apparently saw nothing wrong in self-enrichment through the privileged information they had about the war.

Cadogan was near to Marlborough and knew the likely next move of the general and his army. The pair could then use this information to bet on the results of the military campaign, and buy and sell stocks that fluctuated with the fate of the war. They also received a percentage of the money that foreign mercenaries were due in return for expediting its payment; and pocketed the profits from playing with public money on the continental exchange rates.

In March 1707 Brydges suggested to Cadogan that ‘the notice you give me of the intended measures would be of advantage’, since Brydges could then place an informed bet. Cadogan duly informed Brydges that the siege of Charleroi would begin shortly. Since nobody ‘dreams of’ this ‘surely some advantage may be made of this early notice’, he wrote. Brydges then placed several hundred pounds and stood to gain £3000 if the town fell by the end of July; he bet £3500 in all. Delays to the campaign then alarmed the pair, with good reason for Charleroi did not fall and they lost their money. Undaunted they bet (again unsuccessfully) on the capture of Toulon and eagerly sought to beat the market to other news of the war.

In 1709 Cadogan tipped his friend off that peace seemed to be imminent. Brydges immediately saw that they could profit from knowing the date when peace was proclaimed by buying stock that would soar in value on the news though as it turned out, this again proved a disappointment.

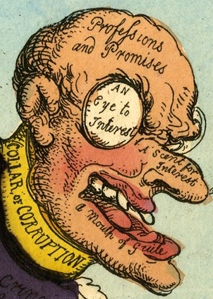

Although their activities were not made public, the Tory-supporting Jonathan Swift came close to identifying Brydges in a pamphlet of 1711, The Conduct of the Allies, which launched a bitter attack on Marlborough and the whole war, which Swift depicted as a sort of conspiracy to make money for his political enemies, the Whigs. Attacking Churchill, he wrote: 'whether this was were prudently begun or not, it is plain that the true Spring or Motive of it, was the aggrandising of a particular Family'.Swift also talked of ‘the creature of a certain great man, at least as much noted for his skill in gaming as in politics, upon the base mercenary end of getting money by wagers’. Even so, Swift did not name Brydges, though he probably had him in mind when writing these words.

James Brydges first duke of Chandos by Herman van der Myn © National Portrait Gallery, London

Neither Brydges nor Cadogan, who had both profited hugely from the war in ways beyond the wagers they placed on the results of campaigns, were prosecuted. Although Brydges was attacked in Parliament in 1711 (when a £6.5m hole was found in his accounts) he had cleverly swapped sides, survived the attempt to ‘blow him up’ and even became a duke in 1719. But Marlborough was attacked more vigorously. In December 1711 Marlborough was accused in Parliament of profiting from the war, through the contract he had to supply the army with bread and by raking off payments from the foreign troops; he chose to go into exile in 1712 rather than face impeachment proceedings that may well have followed. He had long had a reputation for favouring money and his own advancement, though others saw him as a military hero who had helped save Britain and Europe from French tyranny.

The corruption scandals of the early eighteenth century occurred at a time when integrity in public office was coming under increasing scrutiny as well as being used as a political weapon in the partisan war between the parties. But rather than things getting better, Britain took a plunge into deeper corrupt politics during the administration of Sir Robert Walpole (1721-1742), who earned the reputation of being ‘the father of corruption’. Let’s hope the most recent scandals head us in a very different direction.

Mark Knights

Mark Knights

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…