Unexplained Wealth

Today’s Economic Crime bill extends the reach of an ‘unexplained wealth order’ (UWO). This enables the government to confiscate assets thought to derive from corruption or money laundering, something that seems a relatively recent idea. UWO’s have their origins in the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 which introduced Civil Recovery Orders (CROs) which permitted the confiscation of criminal property using a lower “civil” standard of proof. Instead of needing to prove a crime was committed, law enforcement bodies only needed to show a court that on the balance of probabilities (or “more likely that not”) unlawful conduct had occurred. But to cover instances when even a prosecution was undesirable or impracticable, UWOs were introduced via the 2017 Criminal Finances Act, partly as a result of pressure from Transparency International. UWOs allow for a court order requiring someone to explain their interest in property and how they obtained it; failure to comply can then lead to confiscation.

But these issues have a much longer history, as two East India Company cases (one eighteenth and the other, nineteenth century) illustrate. The idea of unexplained wealth orders was aired in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, even if at that time it failed to find support, in part because of Britain’s nervousness about undermining the sanctity of property.

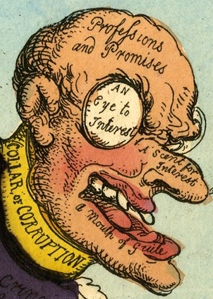

Sir Thomas Rumbold, about whom I have written earlier, was the subject of a parliamentary ‘bill of pains’ in 1783 which claimed that the money Rumbold had sent back from India – many thousands of pounds - should be ‘considered proofs of a corrupt acquisition of his fortune’. Rumbold nevertheless successfully resisted attempts to force him to reveal what he saw as his ‘private’ accounts.

There are interesting similarities between Rumbold’s case and that of Mordaunt Ricketts, Resident at the Court of Lucknow. His case highlights the challenges involved in enabling authorities to investigate the private affairs of those suspected of corruption, and whether such people should be considered ‘innocent until proven guilty’.

Ricketts was born into a well-connected family and, as a result of some high-placed patronage, was appointed Resident at Lucknow. This was the wealthy and luxurious capital of the Kingdom of Oudh, a nominally independent state that was used by the British as a buffer state over which they sought to exercise a large degree of control. Ricketts’ duties included crowning the King in a pageant that included 400 elephants and the close relationship between the monarch and Ricketts seems to have continued for many years, even after the latter left India (see a miniature portrait he received as a gift). One visitor to Lucknow noted that the inhabitants regarded him as ‘a parent and a friend’ and shed ‘many a tear’ when he left in 1829.

Panoramic painting in three sections, illuminated, Illustrating the state entry of Ghazi ud-Din Haidar (nawab 1814-1819; king 1819-1827) of Oudh passing through the crowded streets of Lucknow

Ricketts both married into corrupt money and faced allegations himself. In 1825 he married Charlotte, the wealthy widow of George Ravenscroft who had been collector of land revenue in the Cawnpore region and had absconded with large sums out of the treasury. In 1829, shortly before a planned return to England, Ricketts was told that he was himself the subject of corruption allegations. He nevertheless decided to board ship rather than remain to face down the charges which related to unexplained wealth accrued during his time at Lucknow and to monetary bills ‘drawn in his favour for great sums of money on the Company itself’. Amongst other things, Ricketts was accused of sending far larger amounts of money back to Britain than his salary could have enabled him to save. In June 1834 he was formally dismissed from the East India Company’s service, even though he had already retired. The Company had decided that not to punish ‘the strong presumption of guilt’ would have set ‘an example of the impunity of official misconduct highly prejudicial to the public service’ and ‘be adverse to the first principle of Justice’.

Ricketts was stung into publishing a Refutation of the Charges to try to vindicate himself from the allegation of ‘personal corruption’. He argued that the accusations lacked proof, that he had not been heard in his own defence, and that he could not be expected to open his private accounts, as the Company had demanded, for public scrutiny - something he saw as ‘tyrannical’. His refusal, his insisted, should not be considered grounds for suspicion, since it was wrong to jump to the conclusion that the mystery money must be dirty. The Company, he was adamant, had ‘no title whatever, to make inquisition into my affairs’. He refused ‘this unprecedented call upon me, [which] resolves itself into a claim, that I should forward my private account books to Government, to shew whether they may not contain matter implicating myself’. To surrender in this way was also to sacrifice ‘one of the best features in the character of an English gentleman’.

The Company retaliated with counter-claims. Any honest man would be happy to disclose his accounts, they argued, to clear his name – something necessary given the rumours of Ricketts’ corruption that swirled round India. The paper also attacked ‘a class of twaddlers who, having the phrase “no man is obliged to criminate himself” by rote, constantly apply it on every occasion’. The maxim was, the paper added, one of those ‘judicial fallacies’ for if there was a way (short of torture) to get a criminal to confess falsehoods, ‘its adoption would be defensible by every just principle of criminal jurisprudence.’ By refusing to disclose his accounts, Ricketts ‘voluntarily registered the consciousness of his own dishonesty’.

But it was Ricketts who won. The Company never forced him to disclose the origins of his wealth and never recovered any of it. It was even forced by a High Court ruling to continue paying his pension. Ricketts bought a stylish house in Cheltenham and threw himself into the social scene of the spa town, including heading the Freemasons and helping to found the Cheltenham Horticultural and Floral Society. He also acted as patron for a local balls, fetes and banquets. According to the local newspaper, an Indian in full native costume welcomed guests to a ball in 1834, which was decorated with Indian birds and even an elephant’s head.

As the case suggests, the obstacles to forcing individuals to explain seemingly unaccountable wealth proved overwhelming in the early nineteenth century. It would take almost another two centuries for the principles expressed by Ricketts to be reversed. Today, as a result of the outrage provoked by the war in Ukraine, we witness a further strengthening of this significant change of attitude, both legal and political.

Mark Knights

Mark Knights

Loading…

Loading…

Add a comment

You are not allowed to comment on this entry as it has restricted commenting permissions.