All entries for Saturday 28 November 2020

November 28, 2020

Crony Contracts

In the pre-modern period appointments to office and awards of government contracts were often based on patronage, ‘friendship’, nepotism and sometimes straightforward exchanges of money. Are we in danger of slipping back into a seventeenth or eighteenth century world? When even a reporter from the Daily Telegraph thinks that the Tory government emits a ‘stench of corruption’, we should take this question seriously [Madeline Grant, BBC Andrew Marr Show, 22 November 202].

Emergencies, such as wars or pandemics, open the coffers of the state. The need to support the state’s efforts in a moment of need justifies very high levels of spending but then seems to foster loose or self-interested handling of public money that destabilise notions of fair profit, the balance between the public and private interest, and practices of accountability. Cronyism and corrupt contracts become far more possible.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries Britain was engaged in huge expenditure on war. Civil war in the 1640s raised unprecedented sums of money but also headaches about accountability. The parliamentary forces ranged against the royalists created the first system of parliamentary committees scrutinising public expenditure, though there were frequent allegations that money disappeared into the hands of private individuals profiteering from the crisis and officials who abused their power to advantage themselves or their friends.

The second revolution of the seventeenth century, in 1688, propelled Britain into war with France that lasted, more ‘on’ than ‘off’, for the next 125 years. War became increasingly global in nature, as colonisation meant conflict in Europe spread across the world, and consequently state debt increased in leaps each time tensions flared. Contracts were handed out to supply troops with clothing, food and drink, and to financiers to pay the armed forces overseas. But all this was accompanied by what many contemporaries regarded as large-scale corruption. And over a period of several centuries structures were put in place to properly audit the expenditure; to prevent conflicts of interest; to prevent public money from being siphoned off into private hands; and to hold individuals to account for their behaviour in office. The system creaked each time it was put under strain by largescale emergencies; and often further measures were put it place.

Ironically it was the early Tory party, which emerged in the later Stuart period, that worried about the corrosive effect of large-scale state funding that they saw as disappearing into the pockets of their Whig rivals. The first Tory party was in part formed around hatred of Whig profiteering and cronyism. Thus in 1712, towards the end of a long war with France that had seen the national debt rise to unprecedented levels, the Tories argued that partisan self-interest was undermining the national interest. Money, they argued, was being purloined by Whiggish City financiers who became wealthy on the backs of the taxpayer. The Tories prosecuted one of the leaders of the Whigs, the future Prime Minister Robert Walpole, for a corrupt contract awarded to cronies and with built-in kick-backs. Walpole was also said to have presided over an unaccounted hole in the public finances of £35 million. Walpole was slung into the Tower of London for 'a high breach of trust and notorious corruption'. Indeed, throughout his long tenure as prime minister the Tory rallying cry against him was that he corrupted government and the political system. Anti-corruption was a key part of what it meant to be a Tory.

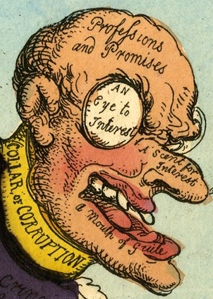

This Tory satire of 1740 depicts Walpole as an overblown idol whose arse had to be kissed if one wanted to get a public office and who was associated, as the words underline, with ‘Corruption’, ‘Venality’, ‘Folly’, ‘Vanity’ and ‘Pride’. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

So it’s somewhat ironic that the Tories today should be the subject of numerous accusations that they award excessively lucrative contracts to cronies without proper scrutiny and fast-track deals for insiders; that they appoint officials to important posts without any public competition; and that ministers are allowed to breach the codes designed to ensure high standards in public life and may even have broken the law in the way they have disregarded due process.

Emergencies always test the systems of the state to prevent corruption, and historically those systems have needed adjustment if they are found wanting. Indeed, after most periods of emergency in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries there was a period of review and reform, and often of significant public anger. We seem to be approaching one such moment again.

For a good discussion about the current dangers of corruption see the Mile End Institute discussion at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k27w9VRE1gI.

For a warning, from the former director of Transparency International, about the dangers of corruption in Britain see https://www.qmul.ac.uk/mei/news-and-opinion/items/corruption-in-modern-britain-the-warning-lights-are-flashing-red--professor-robert-barrington-.html

For the National Audit Office report on government procurement during the Covid crisis see Investigation into government procurement during the COVID-19 pandemic - National Audit Office (NAO) Report

Boris Johnson ‘acted illegally’ over jobs for top anti-Covid staff | Politics | The Guardian

Mark Knights

Mark Knights

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…