All entries for Sunday 24 September 2017

September 24, 2017

Laughing at corruption and the trials of William Hone

Throughout history one of the responses to corruption has been to satirise it and its perpetrators. Satirists in classical antiquity, such as Horace and Juvenal, had sought either to mock or snarl at corruption. Graphic satirists did so in Britain in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, a tradition continued by cartoonists today. But those being satirised – governments or interest groups – have often reacted badly in the past and present to such treatment and sought to close it down.

Two hundred years ago, in December 1817, the radical publisher William Hone laughed at the government for its corruption and so it tried to stop his mouth. He was subjected to three trials in as many days, but, as I explore in a recent chapter in a collection of essays about satire and laughter, Hone emerged victorious from his gruelling ordeals. Hone’s trials raised fundamental issues not only about how far the press had a right to expose and mock governmental corruption but also how far satirists saw themselves as part of a tradition in which free-born Britons had a duty and right to engage in such activity.

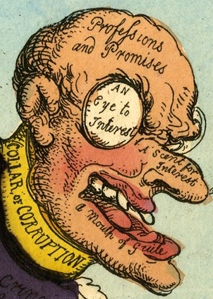

Hone was prosecuted for three mocking parodies, which emulated religious texts - the creed, the litany and the catechism - to ‘instruct’ audiences in the vice of corruption rather than in the pious virtue of integrity. The Sinecurists’ Creed attacked those who held ‘a place of profit’ for which their only duty was to perform loyal duties to the government; and The Late John Wilkes’s Catechism had a central character, Lickspittle, who is instructed how to become ‘the Child of Corruption’. A third piece offered a satrircal Political Litany. The government alleged that religious texts should never be used to mock in this way, since to do so in turn mocked religion, and that Hone was therefore guilty of blasphemy. Hone’s defence was that religious parody had been used since the sixteenth-century Reformation -even by the great reformers such as Luther - and he produced print after print, of text and image, to prove his point. Hone was acquitted in all three trials, a victory both for the freedom of the press and the capacity of satire to puncture corruption. Indeed, Hone went on to produce more radical, popular attacks on what he saw as the systematic corruption of both the government’ s ministers and the system of politics operating in his day. Perhaps the most famous was The Political House that Jack Built (1819) which parodied a nursery rhyme to lash the ‘vermin’ who infested politics.

For Hone, and many others, satire was a particularly appropriate genre to use against corruption. Satire was a way of reforming vice by exposing, ridiculing and shaming it. And it could be used against individuals who engaged in corruption as well as the vice of corruption itself. Satire also uncovered the hypocrisy that often lay under secretive corruption that hid under a thin veneer of legitimacy. Satire drew some of its comic effect from the incongruous juxtaposition of the corrupt inner man and his outward profession of integrity. But besides being entertainment, satire could also unleash powerful emotions of contempt, disgust and anger. This meant that it was a genre that could be prone, at least in the eyes of those being attacked, of excess. If satire was necessary to correct vice, it could, critics argued, also be abused: ridicule could inspire undeserved contempt and even corrupt the people with false notions undermining of authority. Hone’s trials, which are being re-enacted in an eighteenth-century setting as part of the Warwick Words History Festival in November (click here for ticket details), explored such issues as they put parody in the dock.

leftL Lilburne 1646; Right, Hone, 1821

leftL Lilburne 1646; Right, Hone, 1821

The trials also showed that Hone’s ‘age of reform’ had not only to be fiercely fought for at the time but also stood on the shoulders of at least two centuries of literary and political culture. Hone brought armfuls of old pamphlets and prints into court, dating back to the 1600s and 1700s as well as the 1800s, in order to show the importance of parody as a means to reform religion and to attack political corruption. His particular hero was the mid-seventeenth century radical John Lilburne, whose output he assiduously collected. Lilburne, like Hone, saw citizens as being subject to corrupt authorities; and Hone modelled his heroic self-defence on Lilburne’s own 1646 trial. Hone later wrote that when he read Lillburne's own account of his trial he felt ‘all Lilburne’s indignant feelings, admired his undaunted spirit, rejoiced at his acquittal … This book aroused within me new feelings and a desire of acquainting myself with Constitutional Law.’ For Hone, the turmoil and corruption of the 1810s found echoes in earlier reformation and revolution. Britain’s nineteenth-century struggle for reform thus had very long roots that Hone’s trials help us to appreciate.

Mark Knights

Mark Knights

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…