All entries for Wednesday 11 May 2016

May 11, 2016

Scandal or reform?

The impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff, the concurrent Mensalao affair over payment of public funds to Congress members on key votes (which has convicted 25 politicians, bankers and businessmen), and the investigations into kickbacks by the state oil company Petrobas have put corruption firmly at the centre of political struggles in Brasil. My blog of 23 Feb 2015 explored a parallel set of circumstances in late seventeenth century England, when in 1695 Parliament investigated money flowing from the East India Company to influence politicians and there were similarly polarised positions. Here, however, I want to step back from the Brasilian case and explore a related paradox: allegations of corruption are inherently political but reform of corruption is probably best advanced when taken out of the political arena, except in so far as reforms have political support behind them to make them stick.

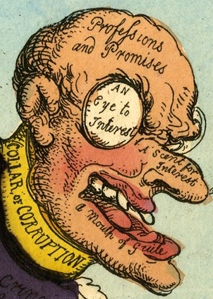

Britain’s own history of anti-corruption shows that accusations were often politically motivated or rapidly acquired took on highly politicised dimensions. Indeed nearly every impeachment in Britain, from that of Francis Bacon in 1621 (when impeachment was revived specifically to prosecute corruption) through to the final impeachment of Lord Melville in 1805/6 (again on corruption charges) was politicised. Impeachment, by its very nature, was a trial by Parliament and hence placed the pursuit of justice in a court that was inherently political. Indeed, arguably that was the point: impeachments were pieces of state theatre, in which public humiliation and retribution were on offer as much as an investigation of the facts. Impeachments attracted big crowds (we have some of the tickets for admission to these spectacles) and a lot of public attention. They can be important in stimulating public debate about what constitutes corruption and they may also hold prominent individuals to account. But impeachments, as the ultimate sanction against corrupt officials, were also not a very effective way of dealing with systemic abuse. They tended to reduce systemic issues to personal attacks; they dealt with scandal rather than reform. Hence once the individual miscreant had been dealt with, the system as a whole continued tended to continue more or less unreformed. Impeachments tended to suggest that the bad apple was the problem, not the barrel.

A ticket for the impeachment of Melville in 1806

Systemic reform came about either through a trauma of the state such as civil war or the loss of a war (neither of which make great policy recommendations) or when non-political bodies that nevertheless had political support were given a remit to reform. The best example is the commission of public accounts set up in the 1780s after the loss of the American colonies had shocked Britain into a political, moral and administrative review of the nature of the state. The first commission (instituted after a gap of 65 years) was set up by Lord North in 1780 and produced a series of reports; in 1785 William Pitt’s administration created a new department for auditing public accounts. Many of these administrative reformers have been forgotten by history – some of them, such as Thomas Anguish who wrote most of the reports in the early 1780s, don’t even merit an entry in the otherwise all-encompassing Oxford Dictionary of National Biography – yet their reports on a range of governmental departments, suggesting ways to improve efficiency and remove corruption, were very influential and mostly implemented by Parliament, even if not immediately. Sometimes it is the non-politicised, thorough examination of practices that does more to tackle practices condemned by the more showy and spectacular state trials. Finally it is interesting that the 1780 commissioners did not mention anti-corruption as their aim: their objectives were ‘the reduction of the expense to the public for the management of the revenue’ and ‘the introduction of a more simple, regular and accordant system into the internal frame of the office’. Avoiding the language of corruption was one way of de-politicising their objectives, since it reduced the need to find fault or lay blame.

Mark Knights

Mark Knights

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…