All entries for Saturday 02 June 2018

June 02, 2018

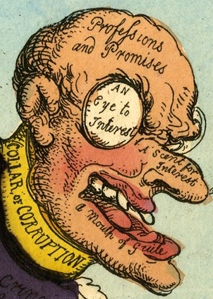

The History of Anti–corruption

The Long History of Anti-Corruption

There is a tendency amongst some to assume that anti-corruption strategies and campaigns are a recent phenomenon. This is partly based on the idea that it was only in 1996 that the President of the World Bank declared that ‘we need to deal with the cancer of corruption’ and that a series of NGO conventions against corruption were devised only in the late twentieth century.

Yet a new collection of essays – Anticorruption in History: From Antiquity to the Modern Era edited by Ronald Kroeze, André Vitoria and Guy Geltner (Oxford University Press, 2018) – shows that anti-corruption has a very long history, stretching back at least to classical antiquity.

The volume arose out of the ANTICORRP project, which sought to investigate anti-corruption through an interdisciplinary perspective. The essays are valuable because historians have been relatively slow to explore the topic, and policy makers and social scientists have (until very recently) tended to be relatively uninterested in historical data. So the possibility now exists of a more fruitful dialogue.

The essays in the volume suggest that debates about corruption were very active before ‘modernity’; that corruption was often a politicised allegation; that anti-corruption was closely linked to ideals of good governance; and that contexts of time and space were extremely important in shaping anti-corruption. The volume shows that even the European experience of anti-corruption has been very different, and was contingent on context.

My own contribution explores anti-corruption in seventeenth- and eighteenth- century Britain. It argues that although there were interesting periods when reform measures were concentrated, anti-corruption was more of a process than an event and that we might therefore think about anti-corruption in terms of waves of activity. This means that there was no simple or sudden shift from a corrupt pre-modernity to a non-corrupt modernity, or a ‘new’ focus on anti-corruption in the latter. The British experience also suggests that anti-corruption took different forms at different times to meet challenging circumstances in evolving political, religious, administrative, legal, economic, social and cultural spheres.

My chapter also seeks to identify a series of factors – some micro, some meso, others macro – which both facilitated and hindered anti-corruption. I suggest that anti-corruption was restrained by inadequate safeguards for whistle-blowers; that scandal could focus on individual misbehaviour rather than structural reform; that social and cultural norms changed slowly; that paradoxically war both opened up opportunities for corruption and created pressures and crises that led to anti-corruption; and that legislation and rules alone had only limited effect. The chapter ends by considering some of the ways in which British national identity was nevertheless increasingly constructed in terms of standards of integrity and honesty.

Other essays in the volume consider the differing experiences of France, Italy, Spain, Denmark, Holland, Germany, Sweden and the Ottoman Empire. This comparative framework (and some of the essays are explicitly comparative) across time and space will become increasingly important in showing different traditions and contextualised solutions to apparently similar problems. Collectively, they raise interesting questions about how far universal measures fit all contexts.

© Trustees of the British Museum

Mark Knights

Mark Knights

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…