All entries for Friday 01 October 2021

October 01, 2021

The Value of History to Understanding Quality of Governance and Anti–Corruption

What can the historian offer those interested in the study of corruption? In this recently-published chapter I show how a historical approach can offer a productive and useful data set and tools to understand corruption and anti-corruption. Since corruption has existed across time and space, and is multi-faceted, involving politics, economics, law, administration, social and cultural attitudes, it can best be studied in a multi-disciplinary way that includes the study of the past as well as the present.

A historical approach offers ways of thinking about change and continuity, and hence also about how and why reform processes occur and are successful. Historical case studies can test and challenge social science models but also offer different, more qualitative, evidence that can help us to reconstruct the mentalities of those who refused to accept that their behaviour constituted ‘corruption’, as well as the motives of those bringing the prosecution or making allegations. Historical sources, often offering multiple perspectives of different participants, can also enable us to form a more holistic view of corruption scandals and of the important role of public discussion in shaping quality of government.

If history has so far been a little marginal to cross-disciplinary discussions about corruption and good government, the chapter seeks to make the cse that it might usefully be more included in analysis and policy discussions. The chapter contributes to a very wide-ranging volume, pulled together by the excellent team at Sweden's famed Quality of Governance Institute, that seeks to take a multi-disciplinary approach to the problems of good governance and anti-corruption. More details about the volume can be found here.

Corruption and State Trials

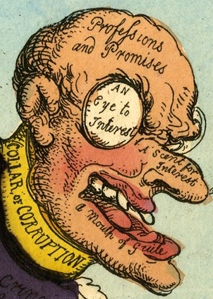

In a chapter just published I examine prosecutions for corruption in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. As well as prosecuting political and religious dissent, later Stuart state trials also targeted corrupt ministers who had been the subject of parliamentary investigations and were subsequently impeached for ‘high crimes and misdemeanours’. Indeed, as Lord Mansfield observed when passing judgement on a corruption case in 1770 and reflecting back on the previous two hundred years, ‘there hardly ever is an impeachment against a minister where the charge is not for receiving money for procuring a grant from the king’. The process of impeachment had been revived in 1621 specifically to deal with corruption allegations against Lord Chancellor Bacon and the device was frequently used over the next fifteen years. It once again became a potent weapon during the Restoration and was repeatedly used until 1725 when a Lord Chancellor was again tried in parliament for corruption.

The chapter investigates these trials in order to show how frequently issues of financial corruption were part of impeachments in the period after the Glorious Revolution and to reflect in turn on what these trials tell us about the nature of corruption more generally in this period. The chapter also analyses the defence arguments employed by the accused, highlighting how appeals to custom and to the letter of the law, as well as attempts to redefine bribes as ‘gifts’ or ‘presents’, were deployed both as a reflection of blurred conceptual boundaries and as a way of neutralising allegations of corruption. Misbehaviour was represented in such defences in terms of norms of friendship, the personal nature of office-holding or cultural factors, and these arguments were symptomatic of those deployed in many other attempts to grapple with early modern corruption. The cases therefore illustrate the difficulties involved in prosecuting this most slippery of crimes, as well as the extent to which its definition was problematic and contested. The chapter also demonstrates that state trials were, by their nature, very frequently politicised, and hence that they were a very blunt way to tackle corruption. For these reasons, impeachments fell into disuse after 1725 until a brief revival once more in the later eighteenth century and early nineteenth century, after which they were permanently abandoned.

Details about the volume can be found here

Mark Knights

Mark Knights

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…