All entries for Thursday 23 November 2017

November 23, 2017

Is the USS really in crisis?

Threat to the defined benefit pension scheme

The employers have said that they want to close the USS defined benefit pension (DB) scheme to future accrual, which means that new members will not be allowed to join, and existing members will not be able to contribute any more into it than they have already built up. Future pensions contributions will all go into a defined contribution (DC) pension pot via the Investment Builder.

Defined benefit pensions are much cheaper and less risky

This is a very bad decision because DB pensions are much better than DC ones. They are a guarantee of a secure 'wage' in retirement for life, whereas a DC pension scheme works differently: it gives a single sum of money on retirement which you have to turn into an income. And pension freedom puts you in the position of having to take some very serious decisions about what to do with this pot of money that will affect the rest of your life. A lot can go wrong, especially as a result of poor financial advice, and you may have to live out your retirement with the consequences of one bad decision.

A DC pension is risky because how much your 'pot' is worth depends on the vagaries of the stock market. Academic research has shown that it costs between fifty percent more and double to provide a given secure income in retirement via a DC pension scheme than than DB.

Essentially, there is less risk in a DB pension because of the collective nature of the scheme. None of us knows when we will die, which is the biggest risk facing us if we are having to live off a DC 'pot': if we do our 'drawdown' sums wrong we might run out of money before we die, or leave unused retirement money as an unplanned legacy if we die earlier than planned. (It is actually rather far fetched to believe we can plan for our retirement in this way.) But actuarial life expectancy tables solve this problem in a DB scheme: the longevity risk is simply pooled.

Likewise it is much less costly to build up a DB than a DC pension because the investments are pooled in a large diversified portfolio, exploiting economies of scale and the law of averages which are not available to a DC fund.

A pension is a 'wage' in retirement for life. A DB scheme is designed to provide that while a DC pension does not. A DC scheme is really an employer-subsidised saving scheme. How you turn the savings you have built up into a pension is another matter that you have to decide and that is not easy or cheap.

The source of the problem facing USS

Contrary to what a lot of people think, the USS is not a government scheme backed by the taxpayer, like the teachers, civil service, health service and others. It is a private scheme run and regulated like a company scheme. It comes under the Pensions Regulator in the same way as, for example the schemes at BT, Royal Mail, British Steel, BHS, etc. Like all these it is 'funded' which means, in effect, that it must stand on its own feet, that its trustees must be able to show the regulator that it will have enough funds to pay the pensions members have been promised and expect every month after they have reitred.

The source of all the controversy about valuing the scheme is the interpretation of the phrase 'enough funds to pay the pensions'. Does that mean a capital sum or a flow of income? The difference has a big effect on how much risk there is.

The UUK have said the scheme must close because it is in deficit, the deficit is growing and that is unsustainable because it means the institutions will have to make ever larger recovery payments.

Let us examine the claims of the UUK. First, the scheme is not in deficit in the ordinarily meaning of the term. Second, there is no evidence that investment returns are too low for the scheme to be sustainable. Third, the scheme is sustainable as long as it remains open and continues into the future along with the universities it serves. Fourth, it is highly questionable that there is a deficit even in the narrow technical meaning in which the word is being used here.

Where is the deficit?

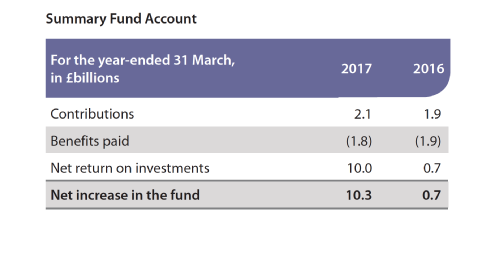

Figure 1 (below) taken from the USS Annual Report for 2017 shows the income from contributions and investments and payments of benefits. It shows that there is not actually a deficit in the usual meaning of the word. Income from contributions by employers and members totals £2 bn, while pensions in payment come to £1.8 bn. In addition it made a return on its investment portfolio of £10 bn (mostly this was from market price movements but that figure includes over £1 billion in dividends, interest, rent etc).

We usually think of a deficit in the George Osborne sense of not enough money coming in to pay the outgoings, necessitating selling assets or borrowing more. The USS is clearly not in deficit. It is cash rich and every year investing its surplus in new assets such as Thames Water, Heathrow Airport, and many other infrastructure projects in addition to traditional assets like company shares and bonds.

Figure 1: Deficit?

Will there be a deficit in the Future? Here we must enter the realm of intellectual speculation and deal with economic theorising, market fundamentalism and evidence-free opinion

Looking at one year's figures is not enough since they may not be typical and we need to look into the future. We need to find a way of seeing if there will be enough money to pay the pensions when they come due.

It is not obvious how that can be implemented. We have to do a thought experiment.

Consider a pension payment to a young lecturer early in his or her career, when he or she has retired, say in 50 years from now. There has to be enough funds to pay that. The pension can be forecast on assumptions about longevity, salary growth, inflation and other factors. But how can we tell if will be enough money? One approach is to ask how much will be needed to be invested today to give enough in 50 years to pay the expected pension.

Since the trustees have to be sure that the money will be there, they must be prudent in their assumptions. How prudent is prudent enough? Since nothing is ever certain, if they wish to be very prudent, they cannot rely on contributions from employers or members in the future. Theoretically the scheme could close (maybe all the member institutions go under for some reason we do not yet know) and there could be no contributions. So it is arguably best to err on the safe side and make this assumption.

And they have to decide how the money is invested to pay the pension in 50 years. Since nothing is certain in investments it would be imprudent to rely on risky assets like equities, even though they are almost certain to grow handsomely in a long enough period. Prudence - paradoxically - requires investing in secure bonds, which have a poor rate of return. At the moment the rate of return on government bonds is at a record low level due to the government's policy of quantitative easing.

If we do this calculation for all prospective pension payments, we get a figure for the liabilities. Comparing that with the value of the assets the scheme owns gives the funding level or deficit/surplus.

The liabilities figure is very large because it is based on the very powerful arithmetic of compound interest over long periods of time. It is also very sensitive to assumptions made - for the same reason. And it must ignore a host of real world factors that can change dramatically. The figure for the deficit is very inaccurate and volatile since it is the difference between two very large numbers, the liabilities and the assets, both of which are highly volatile.The deficit figure quoted by the UUK and USS executive has changed by over £2billion in little over two months. This fact alone suggests that this way of valuing the scheme is unreliable: the actual value of the benefits can not have changed in that time by more than a miniscule amount.

Another other problem with this approach, that has not been sufficiently discussed, is that it begs the question of how the capital value of the assets is to be converted into money to pay the pensions - that is, an income stream. That process needs to be spelled out and not just assumed. Can a scheme as big as the USS just sell assets on a large scale if need be without disturbing the market? It seems unlikely.

Are investment returns really too poor?

The UUK give one of the reasons for the deficit that investment returns have fallen. It is certainly true that gilt rates are at the lowest they have ever been, lower than inflation. It would not really be sensible for a rational investor to invest in gilts since that would guarantee losing money. But other investments, particularly equities, produce a good return that would seem to be enough for the pension scheme to continue to be viable, if it continued to invest in them.

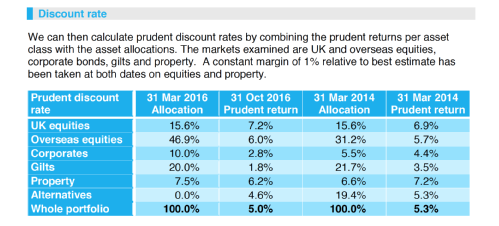

Figure 2 below shows the estimated returns on different investments that were prepared for the UCU by its actuary, First Actuarial. They contain a suitable margin for prudence to enable them to be the basis of a discount rate. The returns have fallen dramatically to low levels on bonds particularly government bonds.

Figure 2: Poor investment returns?

Is the USS unsustainable?

Another thought experiment is to ask if there is likely to be enough cash flow to pay the pensions, based on a projection of income from contributions and investment earnings and liabilities. This is a natural, direct approach that requires less in the way of assumptions than the capitalisation approach described before. In particular it does not require a discount rate for compound interest calculation.

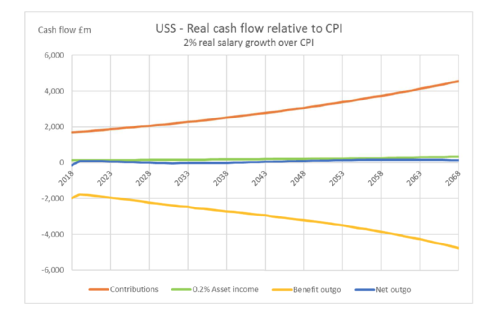

Figure 3, below, shows projected cash flows for the USS that have been prepared for the UCU union by its actuaries (First Actuarial). This is just one of a number of scenarios that have been studied but all show the same picture (2% real salary growth, real asset income of 0.2 percent). It is clear that from this point of view, where the scheme remains open indefinitely, in the same way as is highly likely the pre-92 university sector will, the pension scheme will be perfectly sustainable, having a small deficit or surplus.

Figure 3: Unsustainable?

Is the scheme in technical deficit or is it in surplus?

There is a fundamental difference in the methodology between the situation where the scheme is assumed to be open indefinitely and where it is assumed to be getting prepared to close. In the latter case it must find a way of ensuring it is funded at all times, or at least as soon as possible while it can rely on the employer being able to support it. Volatility of the technical 'deficit' due to market fluctuations in asset prices represents risk here. The risk is that the scheme will close and the valuation will crystallise with assets values low due to a depressed market, such that they are inadequate to pay the liabilities. Hence the need for recovery payments to meet the cost of covering this risk.

On the other hand, if the scheme is open indefinitely with a strong covenant, it can be assumed it will never need to close. Therefore asset price volatility is not important. The ability of the scheme to pay benefits depends on there being sufficient investment and contribution income coming in. Therefore market volatility is not a source of risk. There is much less risk and therefore the scheme is cheaper because there is no need to cover it. Also the scheme does not need to invest in 'safe' assets like gilts for the same reason. An open scheme can, and should rationally, invest in assets that bring the highest return.

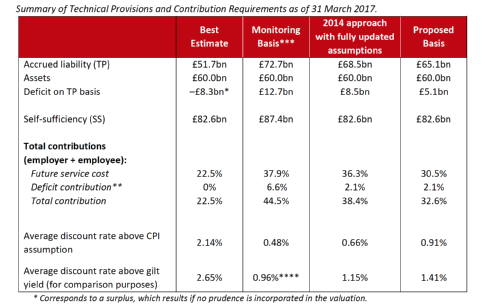

Figue 4 below (from the Technical Provisions Consultation document, September 2017) is the analysis, by the USS executive (not the UCU actuary this time, but the USS exectutive itself under its requirement to provide a fair view of the scheme), of the 'deficit' based on these two different assumptions. On the assumption that the scheme may have to close and therefore must be extremely prudent, so called 'gilts plus', which is the proposed basis, the 'deficit' is £5.1bn. (This has been changed since the TP document was published and is now £7.1 bn. The fact that these figures are so very volatile, with pension liabilities which change very slowly over decades being valued at amounts varying from month to month by billions calls into question the whole methodology.) On the other hand, if the scheme remains open, there is no need to apply a great layer of prudence to all the calculations, and the valuation of the liabilities can be done using the 'best estimate' of the investment returns as the discount rate. On this basis the scheme is massively in surplus, to the tune of £8.3bn!

Figure 4: 'Deficit' or 'Surplus'?

All the efforts of the scheme trustees, the employers and the Pensions Regulator should be devoted to ensuring the scheme remains open. The biggest risk comes from the deficit recovery payments calculated on the basis that the scheme might close. It is therefore a self-fulfilling prophecy. If the scheme is assumed to be ongoing and open then there is little risk.

Risk is not an absolute exogenous quantum as some suggest. It is contextual. And assumptions about it are self fulfilling. The problem with the methodology that is being used is that it is based on an assumption that risk is the same in all circumstances. That is a theory which is false empirically.

Why can't the Pension Protection Fund help?

What is puzzling is that the methodology takes no account of the safety net provided to all pension schemes by the Pension Protection Fund. The USS contributes its share of the levy to this government scheme which guarantees pensions in payment and ensures active members will receive pensions at 90 percent of the DB scheme level.

Why does the USS valuation ignore this? It seems directly relevant since it manifestly limits the risk.

It is said that if the USS entered the PPF it would be too big for it. But the PPF would take on the assets as well as the liabilities. Since the PPF is a government body there can be no problem of it failing to support the schemes in its portfolio, as there is with a private sector employer with a weak covenant. There is no problem with short term market volatility posing a risk.

Therefore we can argue that because the USS is protected by the PPF, a statutory body supported by government, the greatest part of its risk is removed. The valuation should therefore be done without such a large amount of prudence, and therefore the deficit will be much smaller or non-existent. Therefore the scheme is not in danger of failing and of having to enter the PPF.

Can anybody explain why this argument is not being used?

Dennis Leech

Dennis Leech

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…