"When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said in rather a scornful tone, “it means just what I choose it to mean— neither more nor less.” Lewis Caroll

"Words are a wise man's counters, they do but reckon by them; but they are the money of fools." Thomas Hobbes

The UUK consultation document Funding background from the trustee is highly misleading to say the least. It contains statements that appear superficially to have a straightforward meaning in ordinary language but are in fact technical in that they require special assumptions for them to be true. Also some statements are downright false. It also has to be said that the trustee's approach to funding raises the question as to whether the trustee is fulfilling its fiduciary duty to always act in the best interests of members. Here are some of my comments.

Valuation and Funding Methodology

The document says:

Since 2011, the deficit has increased significantly and, based on the current benefit structure (ie without taking any account of the proposed changes), the trustee anticipated that it would report a deficit of approximately £12 billion for the March 2014

valuation."

There has not actually been a valuation as yet, by the way. That cannot be done until the changes to the scheme have been agreed. So there is an important element of circular reasoning here, which is rather awkward: the £12 billion deficit depends on members (via the trustee) agreeing to it.

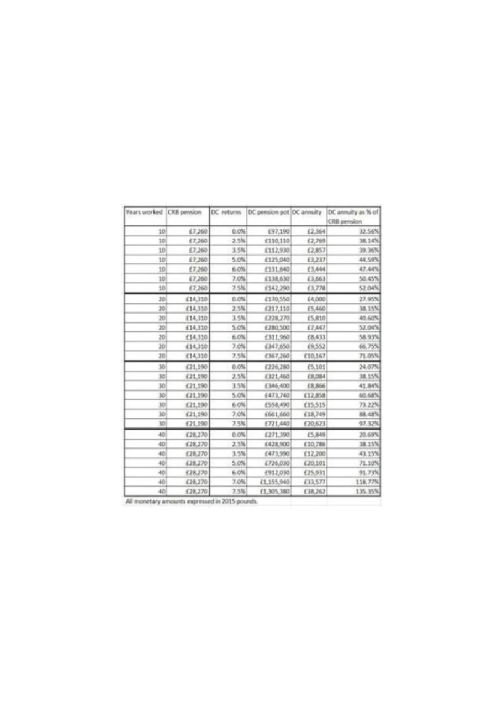

Importantly there is selective use of evidence: the £12 billion figure assumes some changes are implemented but not others. It assumes valuing the liabilities using 'gilts plus' rather than 'best estimate minus' (discussed at length in the First Actuarial report); also 'de-risking': switching from long-term growth investments to lower-return (but less volatile) government bonds. At the same time benefits are assumed unchanged. Both sets of assumptions point in one direction making the deficit bigger and bigger. This is highly tendentious and quite biased reasoning.

Then it says:

... the most significant factor is the change to the assumption which the trustee is making for future investment returns – and the effect of a lower assumption reflecting the changed economic environment – which has added around £7.6 billion to the amount needed to pay pensions."

This does not mean what it appears to say if it is read as ordinary English. The reader might think it alludes to the financial crisis from 2008 on. But investments have recovered since then and the USS investment managers have done well. No. What the trustee means here is how the future pensions promises are valued - a highly technical matter. The USS has to find a figure to stand for a theoretical sum of money in today's terms that would be enough to pay them (assuming it lent securely to the government at low interest rates). Government interest rates - gilts - are not investment returns determined by the market but fixed by the government for reasons of macro economic policy. The term 'future investment returns' has to be understood in this very specific technical sense and is not referring to actual future investment returns that will be earned on the fund's investment portfolio.

This is the nub of the issue. The USS has a large and volatile deficit due to this valuation of liabilities - not poor investment returns. The USS trustee is using extremely low gilt rates for this calculation and not actual investment returns and calling this "the assumption ... for future investment returns".

... it expects those overall returns will be lower given the challenging future economic environment. These assumptions are ultimately judgements which all trustees must make about future anticipated investment returns. These assumptions are reflected in the valuations of scheme liabilities, and in the increased deficits of many defined benefit pension schemes."

What it means by "challenging future economic environment" is that it believes gilt rates will remain low for the indefinite future. The trustee is basing its policy on a myth that currently very low interest rates reflect the "economic environment" notwithstanding that it is being deliberately manipulated by the Bank of England as a matter of policy ("quantitative easing").

The pensions promises that need to be paid have little to do with this "economic environment". Pensions that are to be paid in the future are the same whether interest rates go up or down although they change the valuation of the liabilities a lot. That is why the valuation is inherently so volatile (hence not very meaningful).

The main reason the deficit is so large is that the liabilities valuation increases every time interest rates go down. If interest rates go low enough (and some inflation-adjusted gilt rates are already virtually zero and some actually negative) the liabilities will become infinite. The valuation methodology is fundamentally flawed because it actually breaks down when the discount rate is zero. It is mathematically equivalent to trying to divide by zero.

Life expectancy

The document contains a misleading statement about the pressures due to rising longevity:

Another factor contributing to this increase is the projected improvements to members' life expectancy. The trustee has reported that the changes to the projected life expectancy assumptions between 2011 and 2014 have added almost £1 billion to the amount needed to pay the pensions promised."

This statement appears to imply that there is factual evidence that life expectancy is increasing faster than before. In fact the evidence from the Office of National Statistics tells us that this is not so. But the trustee has decided to increase it nevertheless on the grounds that a survey of other pension schemes conducted by the pension regulator has shown that a majority are assuming a higher rate of improvement in longevity than is evidentially indicated.

So the approach of the USS trustee is to follow the herd. After all, whatever might happen to the USS, nobody could reasonably blame the trustee. They are only following John Maynard Keynes' dictum: “Worldly wisdom teaches that it is better for reputation to fail conventionally than to succeed unconventionally.”

The de-risking plan versus an ongoing pension scheme: planning to fail?

The document then goes on to say:

Additionally the trustee has carried out some work to update its understanding of the potential financial strength of the sector ... concluded that the scheme's reliance on the sector is considerable and should not grow over time.

The trustee has therefore proposed ... to gradually reduce the amount of investment risk in the scheme - over a 20-year period - in order to maintain the overall levels of risk, therefore reliance, on the sponsoring employers."

This is extraordinary. It means shifting investments from return-generating equities (ie financing investment in real productive capacity by companies thereby helping economic growth) into lending to the government by buying bonds. This is estimated to increase the deficit by £4.4 billion (part of the £12 mentioned above) which is the value of investment income foregone. This decision is to increase the deficit deliberately as a matter of policy and its wisdom is highly debatable to say the least.

The fundamental, overarching risk facing any pension scheme is that there will not be enough money to pay the pensions when they fall due. This new 'de-risking' policy does not necessarily reduce the risk of that happening. Indeed it seems if anything it might increase it. By giving up £4.4 billion of investment wealth it could be seen as almost planning to fail.

The trustee is focussing only on investment risk and ignoring investment return. Yet both are equally important to addressing the fundamental hazard of running out of money. The two need to be looked at together. It could well be that increasing investment in equities and long-term return-bearing assets will improve the chances of the scheme meeting its promises. Many actuaries argue against this kind of de-risking on precisely these grounds. (For example.)

There is also the fact that - as a general principle - this approach is harmful to the economy by leading to resources being diverted out of productive investment.

Is the trustee acting in the fiduciary interest of members?

This policy by the USS trustee is not evidence-based. The thinking behind it seems to be untested financial theory intended to be applied to private companies rather than universities.

Given that they are so controversial it is highly questionable whether these decisions are in the best interests of the scheme. It is certainly not the case that there is solid evidence behind them. The question therefore arises as to whether the trustee is genuinely fulfilling its legally required fiduciary duty. Has the UCU, as the representative of members, considered this? As far as I can see there has been no discussion of the possibiity of a legal challenge on these grounds.

Are universites acting in their own best interests as universities?

The policy seems to be based on the idea that the employer covenant with the universities only has a limited period. This seems an extraordinary idea for pre-92 universities with established reputations, a unique role in society and no reason to think they should not continue. Presumably as with so much else in this dispute it derives from the new idea that universities are businesses just like any other in the private sector and therefore must copy as many of their management modalities as possible. The recent introduction of rigorous line management, with targets defined as metrics, firing academics if they faill to meet short term targets, paying vice chancellors CEO salaries, and so on, are all evidence of the zeal with which universities are embracing what they image to be how businesses behave. Applying the same logic to pensions is more of the same. This is a grave mistake because universites by their very nature are public institutions.

One wonders if the university managements have really thought deeply enough about where they are going before responding to the surveys conducted by the USS and UUK.

Dennis Leech

Dennis Leech

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…