Observations from a City expert on the USS proposals: Why Change?

These comments on the USS proposals have been written by John Murray, who is neither an academic nor a member of USS, but has an expert understanding of the issues, having over fifty years of experience in the insurance industry.

A sustained large-scale academic assault on decades of mistaken focus on point-in-time market values and inappropriate discount rates may yield results that strike action cannot.’

(Extract from a letter published in the Financial Times on the 13th March 2018 on the subject of the USS dispute.)

His comments below relate to two recent documents provided by USS Managers, entitled ‘2017 Actuarial Valuation’ dated 1st September 2017 and ‘31 March 2017 Actuarial Valuation’ dated 8th December 2017

Summary

On the deficit

While the derivation of the discount rate applied is far from clear it does appear as though the apparent shortfall results from the managers’ deliberate intention to shift the fund’s investment portfolio to low-yielding government securities. Without this change there would be no deficit.

On ‘De-Risking’ and Collateral Damage

‘De-risking’ appears to consist of changing the investment profile as described above and then back-filling the resultant shortfall by use of the employers’ current deficit contributions of 2.1% of pensionable salaries. The consequent closure of what remains of the ongoing DB scheme seems to be regarded as collateral damage.

On Risk Generally

- Referring to long term investment in equities as ‘betting’ or ‘gambling’ is inflammatory, ill-advised and has no place in a discussion of this nature

- Investing in government securities is by no means risk free

- Nowhere is the risk inherent in the opportunity cost of missing out on potential equity returns addressed

- The risk that members may be deprived unnecessarily of a valuable benefit by reason of the adoption of a low-yield investment policy is never even mentioned

- The only risk that the managers seem to be interested in avoiding is the risk of a problem with the Regulator.

On ‘Self-Sufficiency’

‘It would be difficult to convince the man on the Clapham Omnibus that one achieves self-sufficiency by reducing the income available to the fund’

On Achieving the Stated Objectives

On no common understanding of the terms will the managers’ proposed action achieve the stated objectives of de-risking and securing self-sufficiency.

On the Way Forward

- The direction being proposed by the managers needs to be abandoned

- USS is uniquely placed to seek a derogation from the much-criticised pension rules

- A joint case to make an exception should be put forward by UUK, USS and UCU

Observations on USS Proposals as set out in two documents entitled ‘2017 Actuarial Valuation’ dated 1st September 2017 and ‘31 March 2017 Actuarial Valuation’ dated 8th December 2017

In the notes that follow, the above documents are identified as 9/17 and 12/17 respectively. The latter document is to some extent an update of the former but is much less extensive.

1. Summary and Overview

1.1. Although neither of these papers is presented as a set of proposals for action, but rather as a review of certain suggested valuation assumptions, they very clearly contain implicit proposals that involve a radical restructuring of the USS (the Scheme)’s investment portfolio.

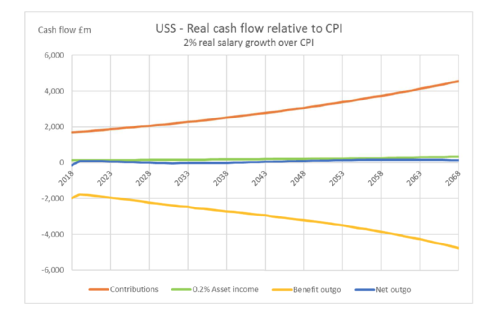

1.2. Boiled down to their essentials, the proposals are aimed (perhaps not directly but certainly effectively) at reducing the investment income that the Scheme will receive in the future, thereby creating a funding deficit. One of the consequences of this action will be the need to remove what remains of the final salary scheme going forward.

1.3. The reasons for this action are given as either ‘de-risking’ or creating ‘self sufficiency’. These notes will argue that the proposed action will achieve neither of these objectives while unnecessarily depriving members of what is left of a valuable benefit.

1.4. These notes also include suggested possible ways out of the current predicament.

2. Introduction

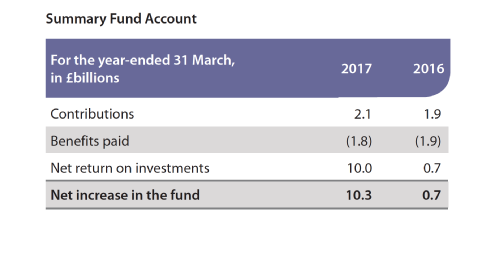

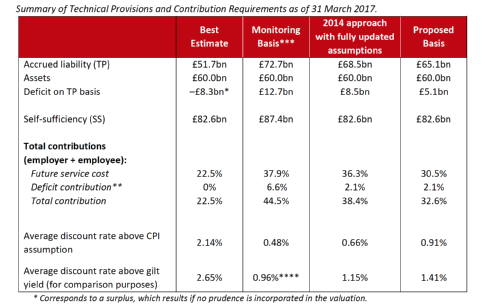

2.1. The Scheme’s financial position is set out below:

USS Funding Position – Gap Analysis

Source: 31 March 2017 Actuarial Valuation dated 8 December 2017

(£bn)

Best Estimate Approved Basis Gap

Accrued Liability 54.8 67.5 12.7

Assets 60.0 60.0

Surplus/Deficit 5.2 -7.5 -12.7

Self-sufficiency 82.4 82.4 0

Mean discount rate

(above gilt yield) 2.31% 1.20% -1.11 (-48%)

2.2 The expression ‘Best Estimate’ in the first column should not be confused with the business term ‘Best Case’. In the Definitions at p 57 of 9/12 ‘Best Estimate’ is defined as ‘The trustees’ unbiased view of the future outcome for different variables without adjustment [or] with margins of any kind. It is consistent with the median (or 50thpercentile) outcome’. This might fairly be translated as business ‘Mid Case’. Moreover, the definition of ‘Discount Rate’ in the same glossary says ‘The discount rate for technical provisions is determined by the expected investment return less a margin for prudence’, so it may be expected that this mid case outcome does in fact contain some element of caution.

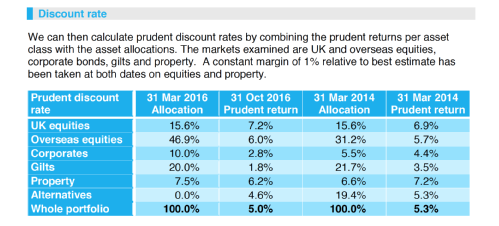

2.3 The term ‘Approved Basis’ might be better described as ‘Managers’ Selected Basis’. The deficit that appears in this column is the result of the lower discount rate employed. But this column should not be confused with ‘Worst Case’. It is not an attempt to see what will happen if the margin above the gilt yield happens to drop by 48%. What it represents is the expected deficit that will result from changing the approach in line with the comments made in the body of the documents. In other words the deficit does not come about as the result of some possible economic downturn but as the direct result of action that the trustees are, by implication, choosing to take. The actual discount rate is not made explicit but is expressed as a margin over the gilt yield. There are several sets of numbers given in the documents but again the mean rate is never made clear. The nearest clue is at p 10 (12/17) where, under the general heading of ‘Investment Return (discount rate)’ it says that ‘This approach therefore includes a provision for a gradual investment de-risking [i.e. moving to gilts or equivalent] to take place over years 1 to 20’. As far as it is possible to tell, this seems to explain the movement in the mean discount rate between the ‘Best Estimate’ and ‘Approved Basis’. The deficit would not, therefore, be expected to arise if things were to remain as they are.

2.4 The expected rates of return on different types of investment presently in use are set out below. The effect of the proposals, basically to shift from equities to gilts, can be clearly seen.

Projected Real Rates of Return (i.e. adjusted for inflation)

Source: 31 March 2017 Actuarial Valuation dated 8 December 2017

Asset Class 30yr Expected

Equities 3.64%

Property 3.23%

Listed Credit 1.45%

Index Linked [Gilts] -0.76%

Cash -0.56%

3. Why the Change?

3.1. The reasons given are described as ‘de-risking’ or seeking to achieve ‘self sufficiency’. The two concepts, as used in the reference documents, are closely interrelated. Self-sufficiency is described at p 58 (9/17) as ‘The value of assets that are required to meet the Scheme’s accrued defined benefit liabilities while adopting a low risk strategy. By a low risk investment strategy we mean one for which there is a low probability of ever requiring additional employer contributions to fund benefits accrued to date.’ Note that this does not include benefits that might be accrued in the future.

3.2. One might well ask why it is thought that self-sufficiency is best achieved by moving to a class of assets that has traditionally produced such a poor return. And also if it is correct to describe gilts as ‘low risk’. These matters are addressed at 4 and 6.

3.3. It is safe to say, however, that this notion (shifting to gilts or similar) runs throughout both documents as though it was a given. Sometimes it is denied, for example at p 43 (9/17) it says ‘The trustees apply a ‘discount rate’ to the liabilities which is based on assumed returns from current and planned future asset allocations. This does not adopt a formulaic approach to setting the discount rate linked to gilt yields’. But at pp 49 & 50 of the same document it says ‘For the ‘self-sufficiency’ and ‘economic’ bases the discount rate assumes a term structure derived from the yield of fixed interest gilts appropriate to the date of each future cash flow (extrapolated for cash flows beyond the longest available gilts) as advised by the Scheme Actuary. For the ‘self-sufficiency’ basis a margin of 0.75% is added’. So practice would seem to differ from theory.

3.4. The real reason for the proposed change is never articulated but it is not too difficult to divine. The objective of the Scheme managers is to switch the investments to what at p 28 (9/17) are referred to as ‘bond like’ investments aimed at producing the gilt yield plus 0.75%, and then to fund the resulting deficit by use of the (employers’) ‘current deficit contribution of 2.1% of pensionable salaries’. This deficit, it is estimated, will be eliminated in eight years (pp 24&25 9/17). After that they hope that the income from the ‘bond like’ investments will be sufficient to ensure that the employers will not need to shoulder any further increase in their contribution.

3.5. It is, of course, inevitable that defined benefits arrangements are discontinued at this stage otherwise, with such a poorly performing investment portfolio, the contributions required to keep these benefits going would be enormous.

3.6. There is a driver behind the driver and that is current pensions legislation which pushes schemes down the gilts route. The essentially flawed thinking behind this legislation is considered at 4 and 7. It is in this area that the real battle lies (see 7.2) and it would be valuable if the trustees could be brought on board. The managers’ intention is to reach some notional ‘safe haven’ whereby if things do go wrong they have assured the trustees that they will be free from any liability because they have followed the ‘safe’ route. This should secure a quiet life for all (except the Scheme members).

4. Investment, Gambling and Risk

4.1. Before moving on to consider a way out of this morass, it would be opportune to take some arguments off the table before they are employed as a counter. It is sometimes contended, for example, that investing in equities constitutes gambling and that using this form of investment is equivalent to ‘betting’ the scheme’s funds on the vagaries of the stock market. As we will see below, there is risk inherent in all types of investment but it is important to differentiate buying equities to hold for the long term and buying and selling in short order with a view to a quick profit: the former is investing and the latter may be considered a form of gambling (like the activities of a day trader). Moreover it is worth bearing in mind that equities, as a class of investment, have outperformed all other forms of investment, including UK house prices, over the long term (and what is a pension fund if not a long-term investment?) or at least in the period from 1900 to end 2017. See Global Investment Returns Yearbook: Credit Suisse (publ.). Talk of gambling or betting is inflammatory, ill-informed and inappropriate in this type of discussion.

4.2. Government bonds, on the other hand, are by no means risk-free investments as is sometimes claimed. Some of the risks involved are implicitly acknowledged in the reference documents but it would be as well to make them all explicit here.

4.2.1.Matching Term Risk

This is acknowledged by implication on p 10 (9/17) where it refers to ‘...cash flow (extrapolated beyond the longest available gilts)...’ Pension funds are very long–term undertakings whereas government bonds have end dates and it is often impossible to match the pension terms with government securities. This risk does not exist with equities.

4.2.2 Assumed Future Interest Rates Risk

There is an assumption by the managers that [bond like] rates will revert to ‘normal’ in ten year’s time (see the jump in the discount rate at year 11 in the table on p 51(9/17) and also p 5 (12/17). At p 8 of document 9/17 it is observed that ‘If interest rates do not in fact revert as forecast to the levels proposed (sic) by the trustees, then future contribution requirements could increase…...’ Well, yes and maybe a stronger word than ‘could’ would be appropriate. This risk is a heavy one and could be avoided. They got it wrong in 2014 when they thought that rates would have reverted by 2017. See p 9 (9/17) ‘Between valuations, long-dated index-linked gilt yields have fallen from already historically low levels by a further 1.5%, making them more expensive than in 2014. As a result the trustees could not de-risk the portfolio under the funding triggers agreed at the 2014 valuation’.

4.1.3 Reinvestment Risk

Because government securities are issued for a fixed period, they are automatically redeemed when the period ends. It is by no means certain that a similar rate of return will be available on issues then coming onto the market. See the remarks about extrapolation of cash flows under Matching Term Risk

4.1.4 Pro-Cyclicality/Availability Risk

If everyone is seeking to invest in bonds then this will drive the prices up and the returns down. This is implicitly acknowledged at p 9 (9/17) also see under ‘Assumed Future Interest Rate Risk’ (above). No mention is made of the fact that, if the government is looking to reduce the level of its borrowing, there is the risk that there may not always be sufficient bonds issued to meet demand. This is already a factor in Germany.

4.1.5 Sovereign Default/Concentration Risk

While the British Government has never so far defaulted on a bond, sovereign default is not unheard of and the future is difficult to predict. Going almost exclusively for government bonds introduces a risk concentration element which does not exist with a well diversified portfolio of equities

5 The Risk that Durst Not Speak its Name

There is a very significant risk that is not even alluded to in either of the reference documents, namely that the members may be deprived of what remains of a most valuable benefit for no good reason. Future history could well show that by maintaining a portfolio of mainly diversified equities sufficient income would have been produced to keep current benefits in place. This is the clear implication of the ‘Best Estimate’ valuation. Trustees owe a duty to every participant and not just the Regulator (as one could be forgiven for imagining reading the reference documents).

6 De- risking and Self-Sufficiency

6.1 So far as concerns the question of removing risk it is difficult to see how the proposals will achieve this, unless one regards equity investments as inherently so very risky that they must be avoided at all costs. But as has been demonstrated above, there are many risks associated with government bonds and it could be argued that the real risk that the planned action will run is the opportunity cost of not investing in equities and so missing out on the returns that have traditionally been available from this source. The only risk that the managers seem to be intent on avoiding is the risk of possible problems with the Regulator.

6.2 It would be difficult to convince the man on the Clapham omnibus that one achieves self-sufficiency by reducing the income available to the fund. It is only the very strange definition of self sufficiency contained in the document (first create a deficit and then seek to back-fill it) that will be secured by the proposed approach.

6.3 There is a powerful argument to say that what is being proposed will achieve neither the reduction of risk nor any degree of self-sufficiency.

7 A Way Forward

7.1 As has been demonstrated above, the proposed approach fails in its objectives and, by way of collateral damage, ends defined benefits going forward. It would be wise, therefore, to abandon ‘de-risking’ and revert to a more balanced portfolio of investments, including a substantial equity element. This will not be so easy to achieve, however. As explained at 3.4 to 3.6 (above) there are regulatory issues to consider. It is most probable that the managers will have intimidated the trustees and convinced them of the absolute necessity of reaching ‘safe haven’ if they are to be sure of avoiding any risk of personal liability. It would not be the first time that such a thing has occurred and the natural caution of the trustees is understandable in the circumstances. Further, the Regulator may be expected to support the managers’ position. The Regulator’s role is to enforce the rules, not to consider the best interests of the scheme members.

7.2 The easiest way to arrest the planned journey to Armageddon would be to seek a

derogation for the Scheme. There are grounds for this. At pp 35 et seq. (9/17) reference is made to the strength of the employers’ covenant. The heading at 1 on p 35 states that ‘The covenant is uniquely robust’ and at 2 that it is ‘........rated as ‘strong [the highest rating] by PwC’. For all the reasons explained in the document this looks to be a fair assessment. One could therefore argue that the Scheme, in its unique circumstances, should be allowed to derogate from the real or implied rules of pensions legislation and to continue with a (truly) balanced portfolio approach. It follows that the trustees should at the same time be granted immunity for any adverse outturn that might follow the granting of this derogation.

7.3 There is already support for this view. In a letter published in the Financial Times on 13thMarch of this year and referring directly to the USS, the joint signatories called for ‘A sustained large-scale academic assault on decades of regulators’ mistaken focus on point-in-time market values and inappropriate discount rates…’ And it should be emphasised that the requested derogation would cost the taxpayers nothing. To have the maximum chance of success the application should be made jointly by UUK, the Trustees and the UCU to the Pensions Minister.

7.4 Another, though less certain, approach would be to see if the trustees could avail themselves of what is known as ‘the business judgement rule’ which is available to members of company boards. This says effectively that directors cannot be held liable to their shareholders for an adverse business outcome if they made the decision in good faith. This can apply even to contrarian decisions such as assuming a rise in oil prices when, in fact, they fall. Broadly the claimant, to have a chance of success, needs to be able to show that the directors acted in their own interests and against the interests of the shareholders or favoured one group of shareholders over another. It is a powerful defence and it might be worth finding out if the trustees could take advantage of it or something similar. If the current advisers still insist on the proposed course of action then it should be possible to find some advisers who will take a different view. After all the shortcomings of the current pension rules and their consequences are well known.

Dennis Leech

Dennis Leech

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…